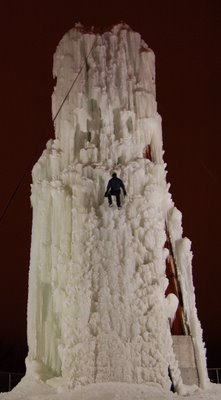

Last weekend I agreed to take part in Festival du Voyageur's Survivor event. Part of the challenge was to sleep in a quinzhee. Here's an expert from my story that ran in the Winnipeg Free Press.

At first the chill was invigorating. The plan was for the three members of my Modern team, part of Festival du Voyageur’s Survivor event, to spend the night in a quinzhee. But as night fell it became clear I had been abandoned. I was the sole survivor, at least on the Modern team.

I checked the accommodations of the Aboriginal team and the teepee was downright cosy. When I walked into the cabin of the Voyageur team, it was practically t-shirt weather as their woodstove glowed red. They were perched on their mattressed bunks, wondering how to cool the place off.

Armed with the testimonials that all quinzhees are toasty warm, I crawled in alone for the night. The floor was layered with woodchips and a bison hide. I spread an extra thick wool blanket on top then unfurled my sleeping bag that promises a good night’s sleep at –15C. Then I set out my thermometer and watched the temperature drop. At 0C I decided to pull another wool blanket over my sleeping bag. At –3C I slipped on my mittens. By –5C I was squirming to put my down parka on over three layers of high tech long underwear then crawl back into my bag. At –8 I pulled my last wool blanket over my head because that fresh air was freezing my nostrils.

I’m not sure when I fell asleep or if I did. I remember checking the temperature one last time and it was –10C. Something was not right. After some investigation the next day, I found that quinzhees are only toasty warm if two things happen—a modest source of heat (perhaps a light bulb) and several other beings to add some much needed body heat to the space. I had neither.

But the game was on and it was breakfast time. Alone, I started a fire in the pit outside the quinzhees. The teams were each given a box of tools and provisions that included flour, lard, baking powder and raisins. As allowed, I had brought a pound and a half of back bacon. Bannock and bacon were on the menu.

With no team members for protection and little hope of survival alone, I was quickly captured by the Aboriginal team and taken to their camp. I didn’t protest much. They had a teepee with a blazing fire. The floor was lined with spruce boughs and the aroma had me dreaming of Christmases past. Plus they already had a pot of bison stew simmering over the fire outside and were searing some bison ribs for s second course. I quickly offered to chop the turnips.

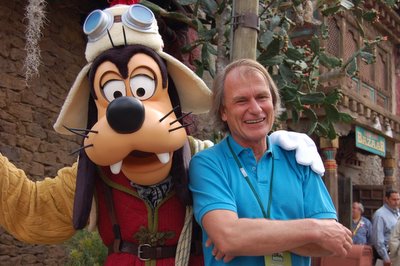

I'm sure you're familiar with the character on the left but any idea who's taking up the spot on the right? That's Laurie Skreslet, the first Canadian to summit Mount Everest. Laurie was along on the Disney media trip to mark the opening of Expedition Everest, the new roller-coaster type attraction in the Animal Kingdom in Florida. I sat beside Laurie on the ride. He giggled all the way. I screamed.

I'm sure you're familiar with the character on the left but any idea who's taking up the spot on the right? That's Laurie Skreslet, the first Canadian to summit Mount Everest. Laurie was along on the Disney media trip to mark the opening of Expedition Everest, the new roller-coaster type attraction in the Animal Kingdom in Florida. I sat beside Laurie on the ride. He giggled all the way. I screamed.